by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

The “global boom” of fact-checking

In the last few weeks the shooting down of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, the Ukrainian crisis and the situation in the Gaza Strip are monopolizing media attention. Such events, for which there is a lot of live multimedia material to check, impose a certain speed of processing and analysis of sources. One of the protagonists of the fact-checking work is Moses Brown, or Elliot Higgins, who has launched his Bellingcat project, which we mentioned here, and that can be funded on Kickstarter until 15 August (so far he has reached £18,000 out of the £ 47,000 needed). His goal is to put together the work of citizen journalists and, through the section ‘How To’, share tools able to debunk false information and certify the credibility of news.

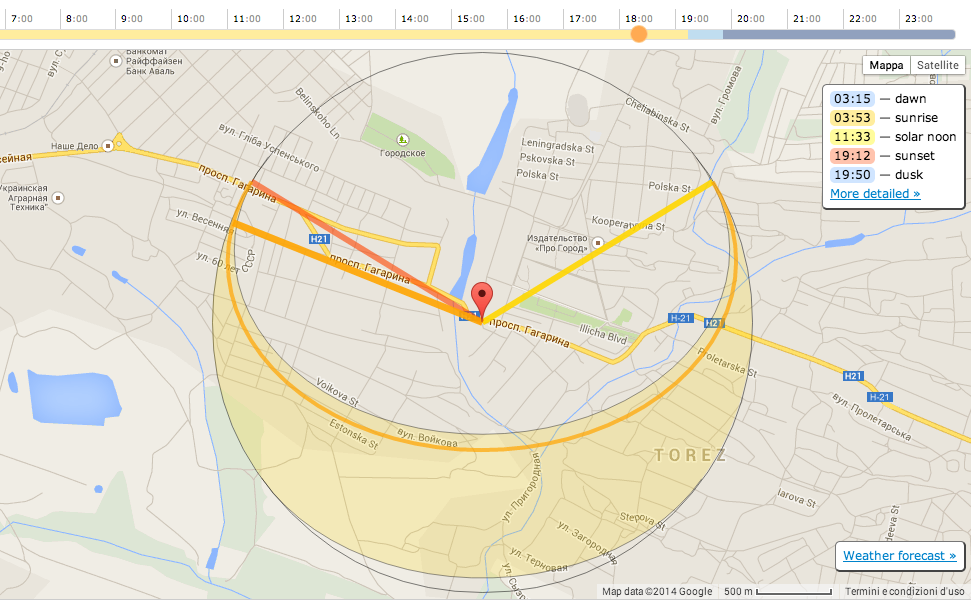

Mathew Ingram of GigaOM has reviewed some of the most useful practices and tools for this type of service. The membership of verification communities such as Storyful (Storyful OpenNewsroom) and Grasswire, the methodical use of social networks like Twitter and Reddit (which has recently opened live blogging), the use of tools to check images like Google Image Search, Tin Eye, and to trace the geographical and temporal location of videos or photos (as Suncalc, Streetview, or client as Checkdesk). Fact-checking, as a spontaneous reaction of the online community to newsworthy events, is a journalistic trend which has recently been growing stronger. It has been analyzed – even in its more political version, checking figures and statements – by Glenn Kessler of the Washington Post, with a report from the Global Fact-Checking Summit which speaks of a “global boom” in the field and contains the most remarkable cases (there is also the Ukrainian StopFake, which we have mentioned here).

“Everything you need to know about” bad habits

To fully understand world events, such those mentioned above, an ‘educational’ upstream exercise is often needed, a kind of introduction to the argument able to inform the reader on issues that even today, after years and repeated attempts, appear ever more controversial. With this purpose, there is a flowering of articles which try to ‘explain everything’ from scratch, following an institutionalized trend (as we saw) of so-called explanatory journalism. Posts titled “All you need to know,” “Everything you need to know,” “X Will Tell You Everything You Need to Know About Y,” proliferate everywhere and Eve Fairbanks of the Washington Post has wondered if these titles and articles are not rather presumptuous and superficial. Reading an “all you need to know” (a kind of “catechism,” according to Jack Shafer of Reuters) is unlikely to be sufficiently comprehensive to allow one to understand all the really essential elements of a given topic.

In a process that replaces the word print with the word click from the famous phrase “All the news that’s fit to print”, some websites – according to critics – are publishing what in their opinion is necessary or essential for readers, instead of ‘limiting themselves’ to providing a good supply of daily news to the reader to allow him to build, brick by brick, his sense of the world.

Last Wednesday the Twitter account of the Associated Press posted this tweet

BREAKING: Dutch military plane carrying bodies from Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 crash lands in Eindhoven.

— The Associated Press (@AP) 23 Luglio 2014

The news was verified, the tweet was not wrong from a grammatical point of view, however there was an ambiguity whereby if the word ‘crash’ is read as a part of the verb ‘crashland’ rather than as a noun, the meaning becomes the plane which was carrying the bodies of the passengers of the MH17 had crashed. A little later, the account clarified the misunderstanding, but the damage was done with the tweet wrongly interpreted and already shared by thousands of people, sparking the most varied reactions. The episode has prompted Megan Garber of The Atlantic to write a piece about the use of “breaking news” designation. According to Garber, it was not a necessary piece of news to add to many others re-launched as indispensable ‘breaking news’ (a plane has landed, after all: it is news in an article, in a context, but not breaking news itself). It is useless to engulf the news ecosystem. “The term ‘breaking’ is quickly losing its meaning,” Garber explains, in agreement with what Felix Salmon stated during the last edition of the International Journalism Festival.

Mashable wants to get serious

Media critics continue to wonder about the future of the profession, the economic sustainability (Steve Buttry on the crowdfunding model), the validity of the paper (David Carr of the New York Times, and Kevin Sablan of OC Register), strategies and format to experiment. This week, on “Trends in Newsroom” of WanIfra the question is if videos could be the best way to serialize news and gain the attention of users, looking at the example of Simon Ostrovsky of ViceNews. Joseph Lichterman of NiemanLab has analyzed – in a post entitled “From Grumpy Cat to Ukraine” – the case of Mashable, an old tech blog that wants to get serious in the territory of news. Since the hiring of the executive editor Jim Roberts (whom we mentioned here), the website has begun to investigate and publish hard news, or at least topics that go beyond the original path, up to the recent examples of Gaza, the World Cup and the Ukrainian crisis.

Roberts, who worked 26 years at the New York Times, is creating a staff of 77 units (30 more than in October, when he sat behind his new desk in Manhattan) and is trying to find a way to get closer to online information, starting from the specific cultural and structural knowledge of the website, aware of the habits and tastes of readers. One of the methods discussed in the piece of NiemanLab is the attempt to combine the sphere of journalism focused on innovation, digital culture and technology (their core business) and classical news, both from the point of view of production (working on texts such as on Snapchat) and thematically. The perfect example, in this perspective, is the blocking of Twitter in Turkey at the end of March, which gave the opportunity to deal with the shutdown like any other news outlet from a different angle, not unlike the ‘ideal’ track of the website, nor too far from the preferences of its readers – generally very young. Today, Mashable has more than 4 million followers on Twitter, 2.6 million likes on Facebook and 34 million unique visits per month.