by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

Vine and videos on Twitter

This week Dick Costolo, the CEO of Twitter, published a culinary video of a few seconds on his social network. It was the official launch of Vine, a stand-alone application (not integrated, to be downloaded separately). It was created by a start-up bought by the San Francisco corporation last fall, and according to many is about to become the response to the purchase of Instagram by Facebook. The application, available now only for iPhone, iPod and iPad, allows the recording of videos of six seconds («apparently the video equivalent of 140 characters») by simply touching the screen and sharing them on various social networks.

According to John Battelle, it would be an evolutionary transition of Twitter from a simple social to a real media company, as shown by the implementation of new services such as the renovated system of embedding tweets. A new ‘era’ that will need more and more care of information. However, according to Mathew Ingram on Paid Content, it risks alienating the company from the effort and the reasons of their early success: the rough essentiality, adapted day by day to the taste and the suggestions of the users.

Videos – for which the progress of the recording corresponds to the pressure on the screen, allowing the user to create a sort of assembly – are played in loop, to emulate the graphic and the journalistic impact of the well-known animated GIF. Jeff Sonderman in Poynter indicated the pros and cons of this new video tool, starting from the potential effects on reporting and the live publication of testimonies. He explains that it is one thing to compare the different photographic points of view of an event, another to look at the different perspectives of the same event with a more realistic tool such as video – with its ‘view’ on all the ethical dilemmas of the case, the crudeness of some content, as already shown in the past with other available instruments. In short, potential drawbacks and benefits are growing, and we must learn to deal with them.

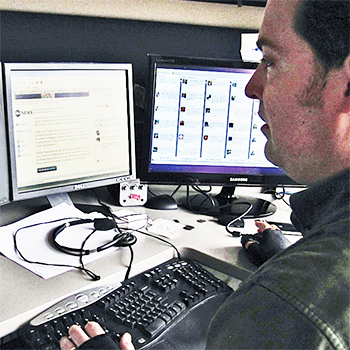

How to use Twitter as journalists

‘Journalists should treat information we gather on social media the same way we treat information gathered any other way’ Steve Buttry said last Monday, in a post about how the experts should check and verify sources and news on social networks. His advice mixes simple common sense and the journalistic practice of checking. Buttry recommends ‘get(ting) hands dirty’ using Twitter as much as possible to identify, recognize and build relationships with sources that can be considered reliable over time. He suggests reviewing, carefully, the profiles of those who provide information – and to ‘sound the alarm’ if they have signed up on Twitter recently or have written few tweets. He also suggests checking the network of conversations of the ‘suspect’ and never forgetting the context, always paying attention to the time, the date and the geolocation – if available – of the tweet.

Finally, it is important to remember to look through the advanced search at other profiles that have reported or are witnesses of the same event in order to confirm the truth, or at least the consistency, of the multimedia contents offered by these types of sources. These operations are certainly not unknown to Andy Carvin, one of the protagonists of the universal journalistic network, who was interviewed this week by Jesse Hicks. Carvin told The Verge how he developed his techniques of verification and instant sharing of information on Twitter. His work made inroads during the mass demonstrations of the so-called Arab Spring. It has been described in his latest book “Distant Witness: Social Media, the Arab Spring and a Journalism Revolution” and in a keynote speech during the 2012 edition of the International Journalism Festival (video).

Considered as «the man who tweets revolutions» (The Guardian), and «one-man Twitter news bureau» (Washington Post), Carvin prefers to be identified as a sort of DJ, or even better a news anchor, who works on «real-time news trying to share the most interesting with his followers». An interview that does not forget to mention critics, such as Michael Wolff for comments on Carvin’s attitude about the shooting at the Sandy Hook School. In the end, Carvin explains what the meaning of ‘knowing how to tweet’ can mean for simple users without journalistic ambitions.

Are journalists joking too much on Twitter?

This is a question asked by Craig Kanalley, senior editor of The Huffington Post, last Wednesday. «I don’t want to come across as humorless. I love to laugh. I think laughter is important in life» Kannalley specifies. «I also follow journalists who I think do a fine job combining humor with their reporting», and really, who doesn’t enjoy laughing?, he adds, before moving on to an accusation that – he admits – he kept for a long time but never made public. If it is true that being a journalist is something serious – and it is one of the reasons for which the author claims to have gone down this road – why is Twitter so full of journalists’ jokes – sometimes related to events which are not happy at all? Of course, Twitter can be a great tool for engagement, good for a community and the recent Sullivan case and contributions of the readers for The Dish is glaring proof. It is a means on which you sign up as ordinary user, as a «human being», although wearing the burden – someone would object – of the valued ‘public’ role you perform, and the fact that each journalist, in some ways, is a spokesman for his/her newspaper.

Last October Ann Friedman, on #Realtalk of the Columbia Journalism Review, referred to the need to ‘humanize’ one’s own journalistic profile on Twitter. «The perfect place for disrespectful comments», «Make more jokes!» was her invitation that seems to have been accepted. According to research by Avery Holton and Seth Lewis of the Universities of Texas and Minnesota, among the tweets of the most popular journalists almost a quarter (22.5%) have a humorous value. Maybe too many, according to the senior editor of The Huffington Post, who remembers how words made public have a weight that can lead to consequences.

Conversational journalism and the community

The additional risk would be to flatten the journalistic personality to the environment where it has decided to ‘talk’ to other users and its own readers, until the difference between media professionals and ordinary citizens was made indistinguishable. The challenge of conversational journalism cited last Thursday by Jason Kottke on his blog is the code of the newest online publishing. «The most visible journalism these days – he begins, citing TMZ, BuzzFeed, Huffington – mostly takes the form of opinionated conversation: professional media people discussing current events much like you and your friends might at a crowded lunch table». With the result that it becomes more and more difficult to understand, in the noise, who is the professional and who the amateur without experience. An idle chatter from which network professionalism may not be able to benefit and which intends to satisfy the tastes of readers, with their colloquial languages used for debates on more easily accessible issues (cases cited are those of Manti Te’o and Beyonce lip-sync scandal). «Speculation is fun and people want their news to be fun».

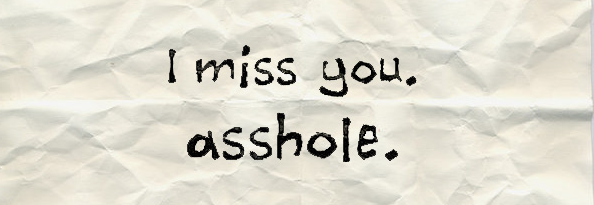

The discussion has a key role for online media and in recent years there have been many newspapers that have decided to choose different policies and methods of insertion of comments, looking for a reliable and open system. In 2011, TechCrunch decided to replace the classic form of comment adopting the one used by Facebook, which requires the authentication of the author to discourage the invasion of the trolls. However, the system has worked ‘very well’ and it seems that the surrender to anonymity has led most commentators not to participate in the discussion at the bottom of the posts. Last Tuesday, TechCrunch decided to give back the opportunity to make anonymous comments thanks to the tool Livefyre – a company that has as its motto «We make your site social». «Commenters, We Want you back» is the title of the post that reports the news. In the image, on a sheet, a handwritten note: «I miss you. asshole».