by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

How Facebook is changing journalism

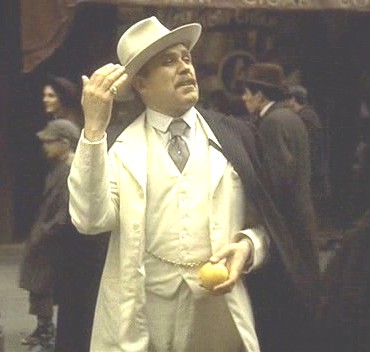

image via

What is the role of Facebook in today’s journalism? The debate has been recurrent in the past few months, and was revived by the Pew Research Center’s study that we discussed last week (the impact of social media in the diet of readers, and how that impact is very strong on their opinions about the news). The issue has been discussed again, this week, gutted by many and enriched by one of the most read and commented articles in the past few days. It is the interview by Ravi Somaiya of The New York Times with Greg Marra, a 26 year old Facebook engineer, among the “people responsible” for the algorithm by which users find the news on their news feed (usually ordered on the basis of the behavior of the members and not in chronological order as Twitter is – for now) and that, indirectly or not, affects the relationship of users with the news and the number of readings and sharing of editorial content.

According to research by SimpleReach, in fact, one in five visualizations on news websites came from Facebook – and the numbers continue to grow. Therefore, it is not a surprise that publishers study Facebook with some interest, trying to get the best possible from it while guarding a crucial area. «People won’t type in WashingtonPost.com anymore,» says Cory Haik, senior editor for digital news at the Post, but more likely they get the news coming from other platforms. Playing by the rules of Facebook becomes almost essential, though Marra tries to distribute these responsibilities on several levels. «You’re the best decider for the things that you care about,» Marra tells the NYT reporter, as if to say that their task is to provide a platform (with 1.3 billion users) and let the content circulate according to the preferences of those who use it.

The truth is that a small variation of the codes that govern these ‘connections’ between likes, posts and users can destroy a publishing and social strategy, or favour another. The cases of Upworthy and Districtify, cited by the author (previously discussed here) are exemplary. By the end of 2013, both of them saw the collapse of their results because of an update in the algorithm that has disadvantaged viral content of low quality.

A matter of trust

image via

However, his interpretation does not convince Jay Rosen. Anyone who works on these codes, he explains, knows that it cannot be so simple. If I were editor of my own news feed, Rosen asks ironically, “where are my controls?” The point of the matter is the contract of a big part of journalistic deployment to “third” platforms. Given this precondition, what would happen if one’s own research and efforts were based on an external service that legitimately decided to concern itself with its own interests? «For publishers, Facebook is a bit like that big dog galloping toward you in the park. More often than not, it’s hard to tell whether he wants to play with you or eat you,» affirms the media critic David Carr of the Times. It takes just a small change in the distribution system to change the cards on the table again. In 2012, for example, the Guardian and the Washington Post experienced the “Social Reader” pages, which allowed an integrated reading on Facebook that made public the preferences of those who use the app (ensuring that all a user’s friends knew what that user was reading). It was a ‘side effect’ that caused more than a little grumbling among members and led Facebook to correct, again, the attempt and make such an approach disadvantageous. “Social Reader” pages died soon, repeating the same mechanism that was already seen with Google. Efforts and money spent on improving the indexing on the search engine – based on the algorithms ‘of the time’ – gave results temporarily, until the construction of a new code.

Carr recalls a meeting with Sergey Brin of Google in which the company offered to cooperate with outlets in terms of technical and commercial advantages. «Sound familiar?» Carr asks. The mechanism, in fact, is similar to what we see today with Facebook, and that brings many news outlets ‘to accept’ Facebook’s supremacy in terms of distribution – especially on mobile – by publishing their content directly on the social network, with no references to the main website (experiments of this kind continue to be numerous: photos, videos, etc. have no direct link to the “head office”). The reason is simple: «They simply can’t afford not to be where the audience is,» explains Lucia Moses of Digiday – and where advertisement makes the money flow. The meaning is to offer content that would not otherwise have had the same exposure, according to Ashley Codianni, who is creating the social Web-only videos for the CNN. Ryan Chittum of the Columbia Journalism Review summarises the debate and warns that it is extremely risky to build models of companies such as Facebook and Google, because in the end – as Carr concludes – if the dog that runs towards you is big enough «he can lick you to death as well.»

«The decline of print is an absolute given»

«Social is a blessing for us,» explained Wolfgang Blau, director of digital strategy for the U.K.-based Guardian News & Media, presenting the new design of the website. «But once someone has discovered us [on the social], we try to give them a destination to come back to more often.» The expansion of its readership base is one of the biggest advantages that digital newspapers, potentially, have in relation to newspapers. With the growing importance of this type of platform – continues the Guardian’s executive editor for digital Aron Pilhofer on TheMediaBriefing – newspapers and publishers have been faced with a double effect: the disintermediation of advertising and content – dominated, as seen, by Facebook – and audience fragmentation. This fragmentation provides «both a challenge and an opportunity for newspapers,» which once thought of their readership as one block, generally for a shortage of data on different kinds of readers who read them. The revolution – if we can still call it so on the threshold of 2015 – is not just technical or instrumental. For Pilhofer it is necessary to rethink how to tell stories and produce content that is as close as possible to what meets the approval of the readers (it is interesting to read “A scarce commodity: trustworthy and relevant information” by Thomas E. Patterson on The Conversation).

How to do it? According to the executive editor, it is essential to push hard on “data driven” production, based on analysis of the data of its readers, so as to offer content that really matters to readers. «Instead of doing things the way we do it now, which is some variation of publish and pray,» he continues – it is necessary to research «an enormous amount of data.» The problem is that «there’s nobody in newsrooms really dedicated to just focusing on this.» There is much reluctance, Pilhofer admits, since many have not yet realized that there are few other alternatives. The decline of print «is not simply inevitable,» he urges, «but it will happen quicker than many expect.» It is not a smoky hypothesis but «it is an absolute given, it’s not like ad revenue is going to come swinging back,» as well as the indexes that are now negative on paper circulation of all newspapers. In history, the decline has never continued long enough to gently tail off to zero. The crisis is profound, irreversible and natural, and the total shift to digital must be completed before it is too late.