by Vincenzo Marino – translated by Roberta Aiello

The moving story of the man with three legs

In early November New York Magazine published a conversation with comedian Jon Stewart, star of the The Daily Show. In the interview, Stewart likened online newspapers, such as BuzzFeed, to those barkers at Coney Island who shout things like «Come on in here and see a three-legged man,» and then show a guy with a crutch.

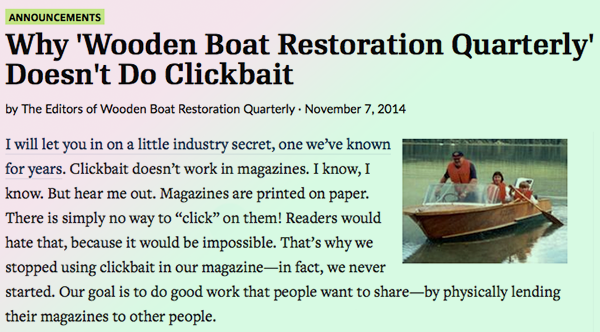

The response of the comic has been interpreted as one of the most lucid explanations of the concept of “clickbait,” an online phenomenon that pushes news websites to exacerbate the titles of their articles to attract readers. Its definition is still very ambiguous, and it has been placed in the center of the debate raised by the reply of BuzzFeed‘s editor-in-chief Ben Smith. In an editorial entitled «Why BuzzFeed Doesn’t Do Clickbait» (subtitled «You will not believe this one weird trick,») Smith defended the work of the website, which has abandoned this reviled technique, since it «stopped working around 2009.» According to the editor, BuzzFeed has not used what is defined technically as “clickbait” because the content of the article is never exaggerated in the titles and the “screaming” promise on social media is always relatively well rewarded.

I’d like to have a discussion with you about clickbait. pic.twitter.com/ceOEJGDW9U

— Ivylise Simones (@ivylise) 7 Novembre 2014

Moreover, Ben Smith clarifies, to continue with the clickbait mechanism and focus on form rather than the content would not make much sense in economic terms. In the current news market, it is the distribution on social networks which is acquiring greater relevance as advertisers count on these dynamics to invest in native advertising and amplify their advertising content (in fact, Smith says, BuzzFeed does not host advertising banners but branded content). In this sense, it is fundamental that a post is interesting at the very least, whatever the title. The readers will be more motivated to share it with their friends, proud of the “discovery,” so as to reach as many people as possible and to increase the so-called “potential reach.” If anything, what the website refers to – Smith continues – is the mechanism called «curiosity gap,» which would entice the reader to click in order to satisfy the delta between the expectation created by the title and its actual content. For many it is the same.

What is clickbait?

via The Awl

The reply of BuzzFeed has sparked more and more irony (here is a Twitter timeline by Mathew Ingram) due to its reputation of frivolous “catch clicks” that the website has gained in recent years, despite investment in hard news. The problem is that the very concept of clickbait is so generic, making life difficult for those who want to denounce abuse or to defend themselves. As noted by Ricardo Bilton of DigiDay, it is like explaining what pornography is. «It’s hard to define, but people know it when they see it. Put another way, if you ask 10 people what clickbait means, chances are you’re going to get 10 different answers.» Bilton has asked what “clickbait” is to some players of the American digital media scenario, getting various answers. From the inclusion of the posts with titles that start with “This town,” or “This celebrity” instead of saying the real names (Alex Mizrahi of HuffPostSpoilers) to low-quality content designed to increase visits (Anthony De Rosa of Circa); from the literal definition of “bait-title” designed to attract readers with content not in line with what was promised in the launch (Julia Turner of Slate,) to the self-indulgence stigmatized by the authors of The Awl («Clickbait is the thing we are not doing).

Clickbait, noun: Things I don’t like on the Internet.

— Joshua Benton (@jbenton) 7 Novembre 2014

According to the Oxford Dictionary, however, clickbait is to be considered the «content whose main purpose is to attract attention and encourage visitors to click on a link to a particular web page.» James Hamblin of The Atlantic analyzes the issue from several points of view. The term has entered the common lexicon with a definitely negative meaning, but are we really sure – Hamblin wonders – that only a title, perhaps a bit too flirty, may define or affect the quality of content? Last August, the paradox was made evident by Clickhole (a satirical website like BuzzFeed that we mentioned here,) which published “Moby Dick” (the book) with a layout as a post of an online newspaper and titled «The Time I Spent on A Commercial Whaling Ship Totally Changed My Perspective on the World» – emulating the clickbaity style of some publications. «Moby Dick is still Moby Dick. But is it also now clickbait?,» asks the writer..

Clickbait is not new; tabloids have long done it; that’s coinbait. Both models seek volume rather than value. — Jeff Jarvis (@jeffjarvis) 6 Novembre 2014

The ”Platonic idea”of clickbait, in general, is not even a novelty. Promotion and/or attractive packaging – at times misleading regarding the content – is practically an implicit mechanism of almost all processes of buying and selling. Nevertheless, it gets more annoying if it creates a system for those who, although commercial, still provide a service – such as journalism, which of course has never failed to make use of similar techniques since there have been newspapers. Hamblin, however, has a theory. If a post has no reason to exist, and was written and released «for the sake of making a thing,» it is clickbait – and BuzzFeed does it, «so does pretty much everyone.»

Anyway, this is «The Only Thing You Need to Read to Understand Clickbait™», according to David Holmes on Pando:

This one weird chart will explain everything you need to know about clickbait http://t.co/SmAdCVVes2 via @pandodaily pic.twitter.com/RJFzHXAwu3

— journalism festival (@journalismfest) 14 Novembre 2014

Understanding the change

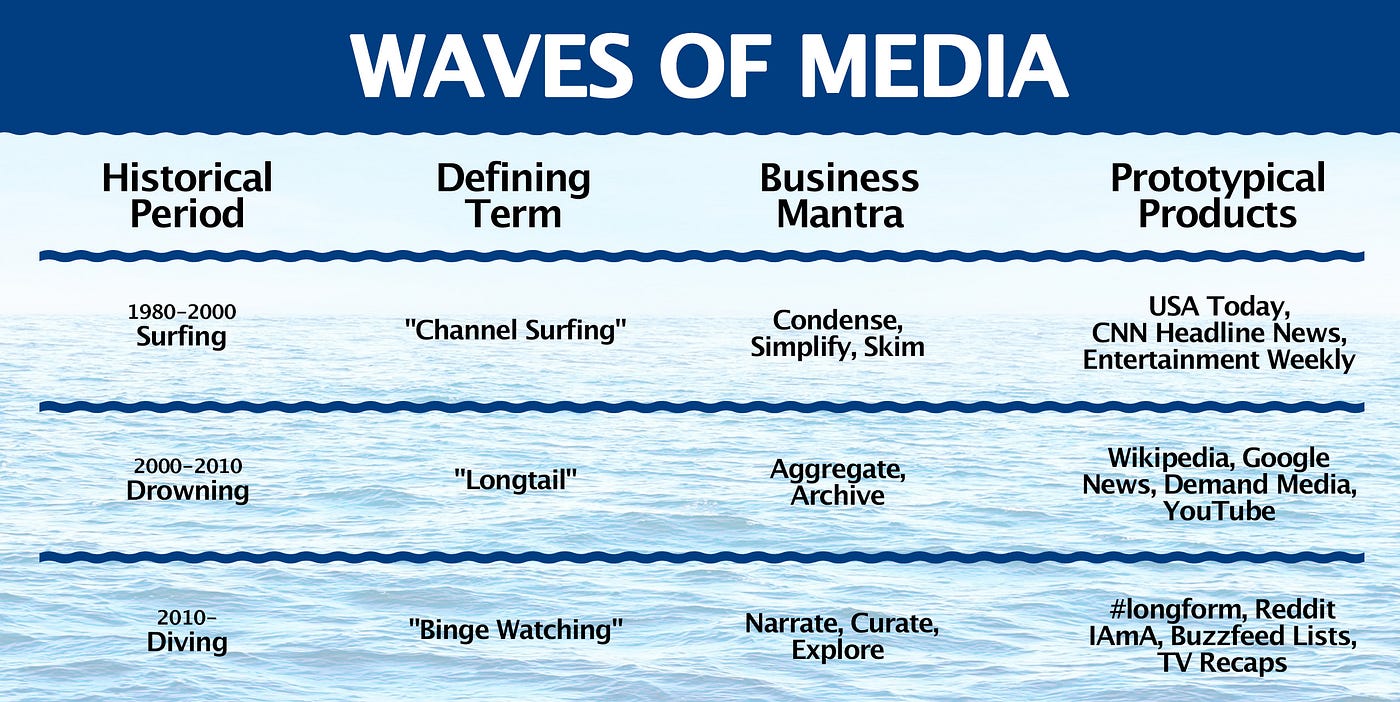

In recent years new media has changed a lot in terms of its function for users, the content it provides and the way it is accessed. If 10-12 years ago the online services (Wikipedia, YouTube, Google News, Netflix Streaming) intended to be an archive in the tide of digital contents, almost drowning the user in a supra-cultural exposure to categorizing, in this new phase – according to the analysis of Rex Sorgatz of Medium – the imperative is to narrate, aggregate, explore with readers (examples: the lists of BuzzFeed, the tv recaps, the cards of Vox, the videos of VICE,) in a sort of guided immersion in the sea of extensive digital content, talking with them and taking care of different niches. In a word, to be meaningful for someone. Jay Rosen of PressThink interprets changes that were there in journalism in recent years, making a list in the post «How to be literate in what’s changing journalism» (which Dan Gillmor tries to integrate on his website from the point of view of surveillance and control of news processes production). Rosen goes from the importance of the distribution on social media to the shift to mobile, from the research of the best business model to the analysis of ‘behavior’ data of the readers who arrive on the homepage, not to mention the focus on transparency, on journalism as a service and on the interaction with users.

Did I mention I made a media timeline!? https://t.co/BTI8P0CSbE pic.twitter.com/f4eCS2cmoa — Rex Sorgatz (@fimoculous) 12 Novembre 2014

The interaction with readers was one of the debates this week, raised by the decision of Reuters to close its website comments section. In an editor’s note, the executive editor of Reuters Digital Dan Colarusso explained the decision due to the change in the habits of the commentators, most recently accustomed to intervene on social networks and not at the end of the articles. «I think Reuters is making a mistake,» says Mathew Ingram of Gigaom in a post. «Even though Reuters is a newswire service with mostly corporate clients, I think the reasoning behind its decision is flawed.» Ingram believes that to move the discussion elsewhere means to give added value to the external platforms (primarily Facebook) for free. This choice is practically comparable to offering the “keys” of the interaction (and the responsibility to punish abuses) by moving the center of the debate – which is not provided to those who do not have a profile on these services – away from the content itself. «A community of readers isn’t just a luxury in today’s environment, it’s a necessity.» The debate, as mentioned before, is open.

commenters-silenced – In the early days of web publishing, commenting sections were a fast, easy way to facilitate… http://t.co/ITLWPEtmqL

— Carla Gentry (@data_nerd) 7 Novembre 2014